One of the joys in designing a tennis house is exploring different ways to make it contextual with the game. A tennis house acts primarily as a gathering spot for players and spectators, and it can be as simple as a court-side pavilion or pergola, providing shade and space for entertainment, to a fully functional building with changing rooms, pro shop and bar. But if it is going to have any relevance at all, it must develop a connection with both the court and the game by being contextual in its use and aesthetics, and engaging for its participants; otherwise, it risks being dull and irrelevant from an architectural perspective as a purely functionary structure that ignores vital design principles.

To be contextual requires a link to both the setting and the game itself by adhering to its outdoor nature, and honoring its history and traditions. Any structure fulfilling this role cannot be a lone, stark intervention with the landscape: it must slowly transcend from the natural environment to its functional role in a progressive and thoughtful manner. And its use of materials must correspond to its particular environment. Furthermore, it must represent aspects of the game and its history to give it relevant meaning.

The tennis house should also engage (which is a part of the game’s long traditions), but not to the extent of becoming a distraction from what is the real focal point of the entire space: the court. By engaging with the court(s), it can serve as a complement, helping define the space by acting as a gateway to the courts, or serving as an anchor or border to the defined area. And just as importantly, it should enable the spectator to engage with the game, making the experience all the richer and interactive. All of these factors are a part of a design that goes back to the origins of the game, and to understand that contextual aspect requires knowledge of the evolution of the game and, more importantly, the court.

Tennis began at the height of the Middle Ages as a diversion for monks bored with their daily chants and rituals, and having a natural need to burn off energy. It was a vastly different game from what we commonly know today. Initially, French monks would escape to their cloisters to hit balls at one another with the palm of their hand, eliciting the name of jeu de paume, or game of the palm. It is still called by this in France as is the famous Parisian Impressionist museum, which was initially a tennis court. Eventually the monks began stringing up dividing nets to induce a level of competitiveness in their play, and the game evolved into what we refer today in the United States as Court Tennis to distinguish it from its more popularly known and youthful cousin, “lawn tennis”.

The original monastic courts were nothing more than the cloisters of a monastery, but as the game developed the courts became more uniform with shed-roofed penthouses, irregular geometry and a variety of windows, or galleries, all of which were incorporated into the game as strategic means for deflecting shots and scoring points. Even today, each surviving court has its own peculiar quirks and geometry but the galleries as intimate viewing spaces remain unchanged.

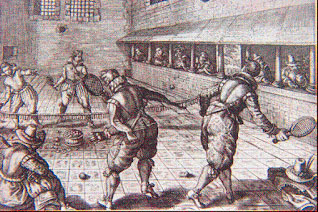

As the game evolved into the Renaissance, it became a favorite of the royal and upper classes, and thousands of courts were known to exist. With the more decadent upper classes playing the game, the scene surrounding the courts took on a more bawdy atmosphere with spectators (as seen in the etching to the right) actively engaging with the players from these intimate galleries that were integrated into the courts. And the game was not without its innuendos and scandals: Shakespeare used tennis as a metaphor in a challenge by the French king in Henry V, while the painter Caravaggio was known to have murdered his opponent over a tennis game. And history tell us that Henry VIII had been playing a casual game as his second wife went to the scaffold to be beheaded – the Anne Boleyn Tournament is still held annually on that date.

As the game evolved into the Renaissance, it became a favorite of the royal and upper classes, and thousands of courts were known to exist. With the more decadent upper classes playing the game, the scene surrounding the courts took on a more bawdy atmosphere with spectators (as seen in the etching to the right) actively engaging with the players from these intimate galleries that were integrated into the courts. And the game was not without its innuendos and scandals: Shakespeare used tennis as a metaphor in a challenge by the French king in Henry V, while the painter Caravaggio was known to have murdered his opponent over a tennis game. And history tell us that Henry VIII had been playing a casual game as his second wife went to the scaffold to be beheaded – the Anne Boleyn Tournament is still held annually on that date.

The term “tennis” is thought to have originated from the French tenez, meaning to receive – a phrase likely to have been shouted out by the server at the start of each point. The word “racquet”, on the other hand, is thought to descend from the Arabic word rahat, meaning “Palm of the Hand” – the head of a court tennis racquet remains asymmetrical, resembling an outstretched hand.

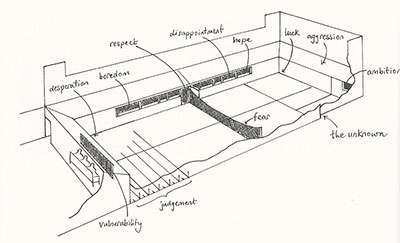

The sketch to the left by the British economist, Kate Raworth, illustrates the layout of a Court Tennis court with its associated viewing galleries and roofs. It provides a sense of the intimacy for spectators with their close proximity to the play. It also cleverly identifies a variety of emotions experienced by players in the placement of different shots: Difficultly placed shots are labeled “luck”, “hope” or “ambitious”. Easier or poorly executed shots have been classified as “boredom” or “aggression”.

The sketch to the left by the British economist, Kate Raworth, illustrates the layout of a Court Tennis court with its associated viewing galleries and roofs. It provides a sense of the intimacy for spectators with their close proximity to the play. It also cleverly identifies a variety of emotions experienced by players in the placement of different shots: Difficultly placed shots are labeled “luck”, “hope” or “ambitious”. Easier or poorly executed shots have been classified as “boredom” or “aggression”.

What does this have to do with the design for a modern tennis pavilion? To be contextual with the origins of the game, the modern tennis pavilion has the opportunity to recapture some of these important themes from its ancient predecessor by engaging similarly with the focal court. Failure to do so makes the structure nothing more than a functional shed that is irrelevant to the history of the game.

Well-designed, contemporary tennis pavilions have taken note of these historical precedents. Consider two excellent examples below: the Queens Club in London on the left, and Seabright in New Jersey on the right. Notice how these buildings provide ample space for spectators that engage closely with the focal court, bringing spectators into active proximity with the play. The connection is strong, and both players and spectators are engaged together in the experience. The buildings are not set apart from the courts but are intertwined with its activity. Each remains a separate entity within the whole program that, in aggregate, defines the space and activity.

Perhaps there is no better design that incorporates the medieval elements to achieve these effects than Stanford White’s Casino in Newport, Rhode Island. Here, the court remains the focal point as the building, with its covered galleries on multiple levels, encloses and defines the overall space much like the ancient monastic courts. Spectators are not segregated off into some high grandstand to be left feeling distant from the play but are intimately engaged as a part of the scene, almost as an active participant.

Including a Clock

The inclusion of a clock tower or wall clock that engages with the court is a contextual element that links the space with its historical roots. Some may conjecture that the clock is there merely to inform players when their court time has expired, but the clock itself is thought to go back to the earliest courts and was integral to the evolution of the game.

It is likely that the monastic courtyards also had a clock tower, and it is believed that the odd scoring system for tennis derived from positions on the clock face (15-30-40, etc). Even deuce is thought to have derived from the French douze, or twelve.

Designers of tennis pavilions in the early half of the twentieth century knew this, and often incorporated a clock tower or face clock into their structure. Look closely at both the pavilions at the Queens Club and Seabright – they have clearly visible clock faces on their facades. Notice as well the dominating clock tower in Stanford White’s design of the Newport Casino which acts as an anchor to the entrance of the inner court.

The Design

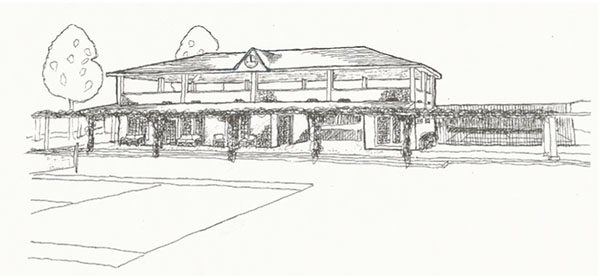

The sketch to the right shows a recent design for a new tennis house based on the principles discussed. It has been designed to serve multiple courts, and functionally includes a proshop, modest changing rooms, an office and storage facilities.

The sketch to the right shows a recent design for a new tennis house based on the principles discussed. It has been designed to serve multiple courts, and functionally includes a proshop, modest changing rooms, an office and storage facilities.

But it also incorporates those principles which are viewed as integral to its success in having meaning to the game and its history. A vine-covered pergola eases the transition from the natural to the built environment, providing a shaded entrance and veranda for courtside spectators. In fact, the lengthy covered pergola extends to the parking area, contributing to that transition and helping to define the overall space of the focal center court which the structure overlooks. Both the lower and upper deck viewing areas allow spectators to intimately engage with the play, with the latter upper deck providing additional viewing to courts behind. And, of course, the inevitable clock face gives context to the game’s rich history.